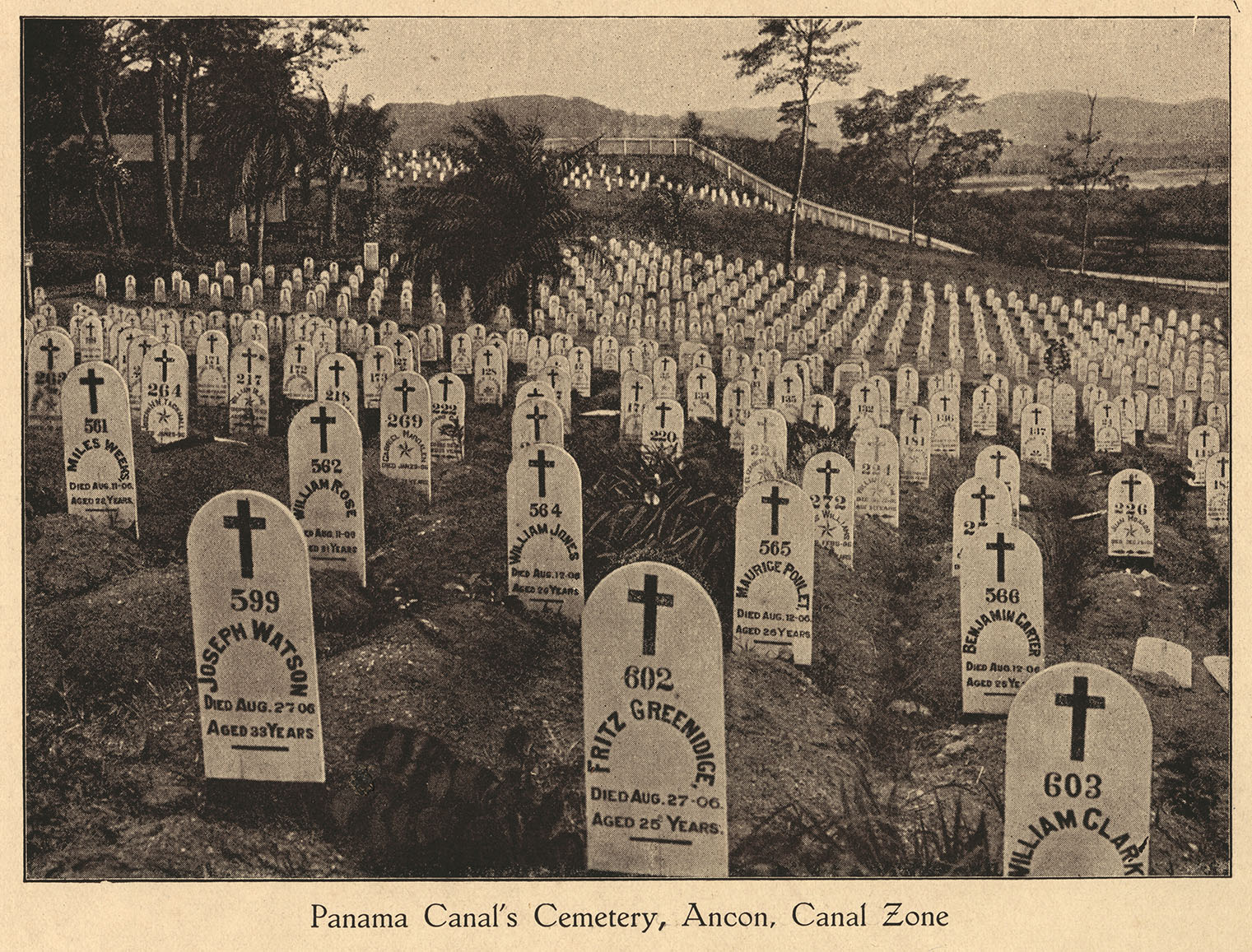

Illness and Death on the Canal

The cost in human lives was the most significant fact in the history of the U.S. and French construction of the Panama Canal. In 1920, Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, described the effects of yellow fever as “defying all precautions, laughing at all remedies.” For every eighty employees who survived six months on the Isthmus, one could say that twenty died. Manual labourers experienced the highest risk of disease and death since their work obliged them to be in contact with deadly insects and reptiles; the safest and highest paying positions on the railroad were reserved for white North Americans.

“Over to Panama, it was the same way—bury, bury, bury, running two, three, four trains a day with dead Jamaica Niggers...It did not matter any difference whether they were black or white...They die[d] like animals.’’

- (S.W. Plume, testimony before House of Representatives hearings 3110, cited in McCollough 1977:173)

The death toll rose higher from 1885 onwards, pushed up by the ravages of yellow fever, malaria, typhoid fever, smallpox, pneumonia, dysentery, beriberi, food poisoning, snakebite, sunstroke, syphilis, tuberculosis, landslides, railroad accidents and suicide. The total number of deaths is unknown.